What is a Contract: Part 3: Conditions - When Is a Promise No Longer a Promise?

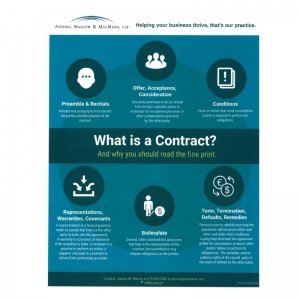

This post continues my series explaining the main elements of a contract, which are outlined on the attached infographic. My goal is to demystify some of these basic provisions to help business owners have a better general understanding of what they are signing.

Another key element of a typical contract is a condition. A condition is an event that must occur or a fact that must be true before a party is obligated to perform his obligations under a contract. Conditions are used to allocate risk by making a party’s obligations, which would otherwise be absolute, dependent on circumstances that are usually outside of that party’s control. The risk of those circumstances not occurring is thus shifted to the other party. For example, your agreement to buy a parcel of real estate might be conditioned on your ability to obtain financing. If you are unable to get financing, you are not obligated to proceed with the sale. Your failure to perform your obligations is excused and is not a breach; the seller will have no claim for damages against you based on your failure to perform. A condition is not necessarily tied to a third party’s performance of an action (such as a bank agreeing to lend money to the buyer) but is sometimes linked to the performance of an obligation by the other party. Some conditions are dependent on weather or similar events that are altogether outside of the contracting parties’ and third parties’ control.

Sometimes a condition is drafted so that its non-fulfillment excuses some, but not all, of a party’s obligations under the agreement. As a result, if the condition is not met, the agreement remains in force as to all other obligations. On the other hand, a condition may be drafted so that the entire agreement will terminate if the condition is not satisfied (such as the property sale example above). It is important to note that the party benefitting from the condition may choose to waive the condition and proceed with performance under the agreement. Further, if the party whose obligations are conditioned performs those obligations even though the condition has not been satisfied, he may be deemed to have waived the condition.

Conditions are not necessarily identified in a single specific section of a contract, but often are sprinkled throughout the agreement where the parties’ obligations are identified. Because of the impact of an unsatisfied condition, it is important to be able to recognize conditions on the other party’s obligations before you enter into the agreement. Look for words such as “if”, “provided that”, “in the event that”, “subject to”, “on the condition that”, “conditioned on”, and “contingent on”.

Before you sign any contract, you should be sure to assess whether any of your obligations should be conditioned on the occurrence of facts or events. If so, it is important that those conditions be clearly identified. Similarly, you should review the agreement to identify any conditions to the other party’s obligations and their impact on the agreement overall and your rights under the agreement. Ask yourself:

• Does the agreement set out unrealistic, vague or unpredictable conditions under which the other party could be released from its contractual obligations to me? Will I have incurred unnecessary expenses prior to the determination whether the condition has been satisfied (e.g., purchase of supplies or services)?

What impact will a release of the other party’s obligations have on my business (e.g., finding a substitute vendor)?

• What actions or omissions (by me or key staff) could result in a release of the other parties’ contractual obligations?

• Are any conditions on my performance needed to provide a way out in the case of prohibitive or unacceptable changes in circumstances down the line?

In summary, contractual agreements will ultimately only yield the intended benefits to your business if they are enforceable, and that means understanding under what conditions some or all of the other party’s obligations might be excused.

Stay tuned for Part 4 of this series, which will move on to the next contract element shown on the infographic: Representations, Warranties, and Covenants.

What is a contract: Part 2: Offer, Acceptance, Consideration: What’s in it for you?

This post continues my series explaining the main elements of a contract, which are outlined on the attached infographic. My goal is to demystify some of these basic provisions to help business owners have a better general understanding of what they are signing.

Moving through the structure of a typical contract, next up is offer, acceptance, and consideration. Together, these clauses define what the offering party is promising to do (or refrain from doing) in exchange for the compensation the other party is willing to pay or provide. They basically comprise the tit for tat, or the meat of the obligations and privileges which are being offered. This is often referred to as a “meeting of the minds.” While this might seem obvious on its face, the devil may be in these details, so it is vital that you know and understand the specific nature of your obligations and be sure that they are sustainable, practical, and likely to result in a benefit to your bottom line or some other benefit to your business. So what can happen when parties fail to clearly memorialize their “meeting of the minds”? Here are a few scenarios that could result:

• The parties might become embroiled in a “battle of the forms”, particularly in the sale of goods context where a buyer submits a purchase order using their company’s form, and the seller responds using their own terms and conditions form containing different and/or additional terms.

• Parties can ask the court to apply certain legal theories to supplement the “four corners of the document” where the intent of the parties may not be clear from the contract itself. For example, even if there is no formal consideration, courts can apply the theory of promissory estoppel to enforce a party’s promise to do something if the other party relied on that promise to his or her detriment.

• Another equitable remedy allows the court to compel a party to make restitution if that party is enriched at the expense of the other party and the surrounding circumstances lead the court to conclude that it is unjust.

• Pennsylvania has a little-known statute called the Uniform Written Obligations Act, which allows the court to infer that consideration exists where the agreement includes language that clearly and expressly states that the parties intended to be legally bound by the agreement.

Stay tuned for Part 3 of this series, which will move to the next element on the infographic: Conditions.

Visit ammlaw.com to learn more about our contract review services, or Joanne Murray.

What is a Contract: Preamble/ Recitals - Let’s begin at the beginning

This post continues my series aimed at explaining the main elements of a contract. These elements are outlined on the attached infographic. My goal is to define the key elements of a contract and to offer some tips and cautions to avoid costly mistakes as you approach these essential documents in your day-to-day business operations.

First up: the preamble and recital sections. The preamble of a contract is the introductory paragraph that identifies the parties to the agreement. It is typically followed by paragraphs known as recitals (also called the background section). Sometimes, these recital paragraphs are labeled “Whereas”. Taken together, the preamble and the recitals tell the who, what, when, and why of the transaction. In other words, they should tell the reader who the parties to the agreement are, the date of the agreement, and what the parties hope to accomplish by entering into the agreement.

As with stories told in other settings, inaccuracies and ambiguities in the preamble and recitals of a contract can cause problems down the road. One of the underlying purposes of a contract is to set forth the agreement of the parties so that their expectations can be enforced by a court or other tribunal. An accurate and detailed introduction to the contract can educate the person who is charged with resolving the dispute as to who the parties are, why they entered into the contract, and what their expectations were at the time the agreement was entered into.

One of the most common mistakes in these preliminary sections of a contract is to incorrectly name the owner of the business as a party, rather than using the entity name. This mistake results in the owner being personally obligated as a party to the contract, which is clearly not the result an owner expects after taking the trouble to incorporate.

While it may be tempting to gloss over these preliminaries without questioning their accuracy, I highly recommend taking the time to carefully review this section in every contract to be sure the story it tells is true and complete. It could prevent costly conflicts later.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of this series, which will move to the next element on the infographic: offer, acceptance, and consideration.

Does That Dispute Resolution Clause Constitute Arbitration Under the FAA?

Reprinted with permission from the June 27th edition of the The Legal Intelligencer © 2017 ALM Media Properties, LLC. All rights reserved.Further duplication without permission is prohibited.

Earn out clauses in business acquisitions are notoriously fertile ground for disputes. Complicated post-closing performance metrics, access to information, modifications to accounting methodologies after closing, tracking and collection of revenue information all present opportunities for buyer and seller to disagree. The classic struggle of seller’s effort to maximize sale return juxtaposed against buyer’s focus on transforming the operations of the acquired enterprise for long term success necessarily create friction. Both sides bring their unique perspectives to the interpretation of the exhaustively negotiated purchase agreement with the new benefit of hindsight.

Certainly, arbitration pursuant to the Commercial Rules of the American Arbitration Association is common in any number of business contracts. When the parties elect that process, they accept the applicable Rules and agree to adopt the procedures which have been developed by AAA. In the earn out or deferred consideration context, however, acknowledging the sheer number of potential conflicts surrounding inherent accounting practices, scriveners often incorporate a unique mechanism for dispute resolution in their transactional documents. When the issue is theoretically limited to a calculation, the parties go to great pains to define the applicable accounting terms and may design a system of dispute resolution which does not contemplate many of the applicable provisions of the Commercial Rules or empower any judicial or quasi-judicial third party to control the process.

Indeed, transactional practitioners have developed language which seeks to avoid the intricacies of AAA arbitration in preference for what should be a predictable accounting calculation based on verified numerical results of operations. In such cases, parties most commonly agree to submit any dispute related to the earn out to an informal resolution process using mutually agreed upon accountants to serve as “expert consultants and not as arbitrators.” The sole purpose of the accountants’ participation is the review of financial information relating to post closing operations and the calculation of deferred consideration; which calculation would be “final and binding”.

You've Got Mail... and Perhaps an Unintended Contract

We’ve all heard of someone who hit the Enter key too quickly and sent an email he later regretted sending. Unfortunately, in some cases, the result is that the correspondents are deemed to have entered into a contract, without a formal writing and even in the face of evidence that the parties intended to later sign a formal contract. That was the case a few years ago when counsel for Amazon.com sent a one-word reply (“Correct”) to an email from opposing counsel outlining several specific terms of a settlement of a lawsuit. A Pennsylvania court faced a similar case in 2006, when it enforced an unsigned settlement agreement between Commerce Bank and First Union National Bank after concluding that the signing of the agreement was a mere formality since the parties had already evidenced their intent to be bound.

Protecting Your Trade Secrets - Silence Is Not Always Golden

A company’s customer lists, price lists, marketing strategies, and other trade secrets are vital to its success. A smart business owner will ensure that key employees sign non-disclosure and non-compete agreements to protect the business if the employee leaves and takes a job with a competitor. But what if the company is sold? Does the buyer enjoy the benefits of the restrictive covenants contained in the selling company’s employment agreements? The answer is “it depends.” In Pennsylvania, if the purchase is structured as an asset purchase transaction, the buyer does not receive the benefit of the restrictive covenants contained in the seller’s agreements with its employees unless those agreements specifically state that the covenants are assignable. This is because these covenants are viewed as trade restraints that impair a former employee’s ability to earn a living and therefore are interpreted as narrowly as possible to protect the employer’s legitimate business interest.