From a Litigator’s Desk: Minority Business Ownership – Know Your Limits

Many an article or blog post concerns minority shareholder rights, shareholder oppression or shareholder “freeze out”. As business and litigation lawyers, we are always mindful of the rights between and among business owners, what can and cannot be done in furtherance of those rights and the legal mechanisms applicable to the exercise of those rights. We frequently write on the strategies available to a minority shareholder such as examination of books and records, claims of breach of fiduciary duty and the potential for appointment of a corporate receiver or custodian.

This is not that article.

The fact is, being a minority shareholder means that, by definition, there are often things you simply cannot control. A shareholder or member in a business entity who possesses less than a controlling stake must have reasonable expectations as to the rights attendant to such ownership and understand the limits of such rights so as to make informed decisions concerning the investment of time, energy and money in pursuit of the collective enterprise.

Let’s start with who owns the remaining shares in the company. In the absence of an agreement to the contrary, the majority shareholder is free to transfer the majority (said another way; controlling) interest in the company without the consent of the minority. A transaction can result in a change in control such that the minority shareholder suddenly works for someone entirely new. While a minority shareholder can enjoy “dissenter’s rights”, such rights are applicable in very narrow situations specified by statute. In fact, in the absence of a prohibition, the stock in a business entity is readily transferrable, just like on an exchange, if a buyer and/or seller can be identified.

Internally, a minority shareholder can find it difficult to impact the direction of the business. Depending on the by-laws of the entity and, frankly, the will of the majority, a minority shareholder may or may not have a voice on the board of directors and thus may not possess a vote on material decisions such as the persons who will fulfill critical roles in the executive branch of the business such as the officers of the corporation. More importantly, a minority shareholder may not have input on the financial operations of the company including distributions, financing arrangements, major purchases of inventory, equipment or talent. All of which can dramatically affect the annual bottom line.

Even employment is not guaranteed to a minority in interest. In the absence of an agreement to the contrary, the employment of a minority shareholder may simply be at will in the same way as the sales force, the administrative assistants or the custodian. Certainly, terminating a minority’s employment could be one of the factors argued in a freeze out, but in the absence of other factors, termination of employment alone may not give rise to a cause of action. Certain courts have suggested continued employment may be implicit in a “founder” but those situations are few and far between and a plaintiff/minority shareholder must be prepared with more to argue than the end of employment if freeze out is alleged.

In business, like politics, being in the minority means sometimes you are powerless to immediately change the course of the company. Sometimes, a group of shareholders can band together to pool their collective influence for their mutual benefit. Other times, the best strategy is to become the majority even when the acquisition of additional shares comes at an unnecessary or unanticipated cost. Under any circumstances, rights afforded to the majority are not constrained solely because a minority shareholder does not agree with a particular course of action.

As a litigator, I am often contacted by minority shareholders who are frustrated by their lack of control or influence. While the law offers certain protection for holders of such minority interests, those remedies are factually limited and are often unsatisfactory even if granted in full after significant expense in litigation. Certainly an appropriate agreement outlining the respective rights and obligations can change the analysis. Business owners should consider, and plan for, what rights their stake in the company provides.

What is a Contract: Part 4: Representations, Warranties, Covenants - The Bones of the Agreement.

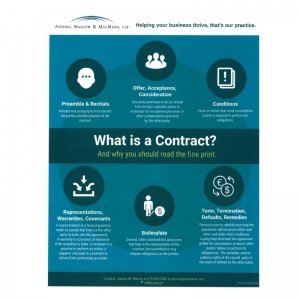

This is the fourth installment of my continuing blog series explaining the main elements of a contract, which are outlined on the attached infographic . My goal is to demystify some of these basic provisions to help business owners have a better general understanding of what they are signing.

This article discusses representations, warranties, and covenants, which are the “bones” of the parties’ agreement. These provisions represent the statements of the underlying facts, mutual assurances, and promises of performance which form the basis of the parties’ mutual understanding. It’s not uncommon to find these concepts used interchangeably in a contract – “ABC represents, warrants, and covenants…”, but the meaning and effect of each of these are quite distinct from one another. It’s important to understand these distinctions so that your contracts accurately reflect the assumptions, obligations, and risks that you are comfortable with.

A representation is a statement of past or present fact (either express or implied) made by one party to induce the other party to enter into the agreement. For example, the seller of a business might represent that gross revenues from the business were a certain dollar amount for the past several years or that there are no claims asserted against the business. If a representation proves to have been untrue when made, the injured party will have a claim of fraudulent misrepresentation if she can prove that: (i) the party making the representation knew or should have known the statement was false when made; (ii) the other party intended the injured party to rely on the statement; and (iii) the injured party’s reliance on the statement in entering into the agreement was justifiable. The injured party can seek monetary damages for its losses or it may ask the court to rescind (void) the entire contract. It is therefore very important to avoid “over-representing” in your contracts.

A warranty is essentially a promise that an assertion made by a party is true, coupled with an implied promise of indemnity if the assertion made by the party is false. As such, a warranty is both present-focused, like a representation, and forward-looking, like a covenant. If a warranty is breached, the injured party is entitled to be made whole; this usually means that the injured party can recover the difference between the value of the contract as agreed upon and the value of the contract in light of the breach. In other words, the injured party is entitled to receive the benefit of the bargain he initially made. The injured party is not required to demonstrate that he relied on the warranty or that the other party knew that the warranty was false when made.

Often, but not always, representations and warranties go hand-in-hand to allow the parties to preserve remedies that are as broad as possible. In complex agreements, the parties usually spend a significant amount of time negotiating how the risks embodied by representations and warranties should be allocated by qualifying and limiting these concepts (e.g., a representation is true to the best of the maker’s knowledge and/or in all material respects).

Product and service warranties are specialized contractual provisions that are actually hybrids of representations, warranties, and covenants. These provisions commonly create limited express warranties that apply to the products or services, identify specific contractual remedies for breach, and disclaim implied warranties that are provided by law.

A covenant is a party’s promise to perform an action or to refrain from performing an action. It relates to the future, as opposed to representations, which are provided as of a specific date. An example of a covenant is a borrower’s promise to make loan payments in accordance with the terms of a promissory note. Covenants can be express or implied. Pennsylvania law imposes an implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing in most contracts.

Stay tuned for Part 5 of this series, which will move on to discuss some possible hidden perils of what is commonly dismissed as “just boilerplate” language.

What is a Contract: Part 3: Conditions - When Is a Promise No Longer a Promise?

This post continues my series explaining the main elements of a contract, which are outlined on the attached infographic. My goal is to demystify some of these basic provisions to help business owners have a better general understanding of what they are signing.

Another key element of a typical contract is a condition. A condition is an event that must occur or a fact that must be true before a party is obligated to perform his obligations under a contract. Conditions are used to allocate risk by making a party’s obligations, which would otherwise be absolute, dependent on circumstances that are usually outside of that party’s control. The risk of those circumstances not occurring is thus shifted to the other party. For example, your agreement to buy a parcel of real estate might be conditioned on your ability to obtain financing. If you are unable to get financing, you are not obligated to proceed with the sale. Your failure to perform your obligations is excused and is not a breach; the seller will have no claim for damages against you based on your failure to perform. A condition is not necessarily tied to a third party’s performance of an action (such as a bank agreeing to lend money to the buyer) but is sometimes linked to the performance of an obligation by the other party. Some conditions are dependent on weather or similar events that are altogether outside of the contracting parties’ and third parties’ control.

Sometimes a condition is drafted so that its non-fulfillment excuses some, but not all, of a party’s obligations under the agreement. As a result, if the condition is not met, the agreement remains in force as to all other obligations. On the other hand, a condition may be drafted so that the entire agreement will terminate if the condition is not satisfied (such as the property sale example above). It is important to note that the party benefitting from the condition may choose to waive the condition and proceed with performance under the agreement. Further, if the party whose obligations are conditioned performs those obligations even though the condition has not been satisfied, he may be deemed to have waived the condition.

Conditions are not necessarily identified in a single specific section of a contract, but often are sprinkled throughout the agreement where the parties’ obligations are identified. Because of the impact of an unsatisfied condition, it is important to be able to recognize conditions on the other party’s obligations before you enter into the agreement. Look for words such as “if”, “provided that”, “in the event that”, “subject to”, “on the condition that”, “conditioned on”, and “contingent on”.

Before you sign any contract, you should be sure to assess whether any of your obligations should be conditioned on the occurrence of facts or events. If so, it is important that those conditions be clearly identified. Similarly, you should review the agreement to identify any conditions to the other party’s obligations and their impact on the agreement overall and your rights under the agreement. Ask yourself:

• Does the agreement set out unrealistic, vague or unpredictable conditions under which the other party could be released from its contractual obligations to me? Will I have incurred unnecessary expenses prior to the determination whether the condition has been satisfied (e.g., purchase of supplies or services)?

What impact will a release of the other party’s obligations have on my business (e.g., finding a substitute vendor)?

• What actions or omissions (by me or key staff) could result in a release of the other parties’ contractual obligations?

• Are any conditions on my performance needed to provide a way out in the case of prohibitive or unacceptable changes in circumstances down the line?

In summary, contractual agreements will ultimately only yield the intended benefits to your business if they are enforceable, and that means understanding under what conditions some or all of the other party’s obligations might be excused.

Stay tuned for Part 4 of this series, which will move on to the next contract element shown on the infographic: Representations, Warranties, and Covenants.

Important Reminder for Home Improvement Contractors in Pennsylvania

In 2008, Pennsylvania enacted the Home Improvement Consumer Protection Act (HICPA) designed to protect home owners from unscrupulous contractors. However, it is also a trap for the unwary home improvement contractors. In addition to its registration requirements, HICPA specifies what must be in a contract for home improvement services and what may not be in these contracts.

HICPA applies not only to contractors performing renovations and remodels, but also many other types of services including most landscaping work, security systems, fencing companies and concrete work. Any individual or company performing these services needs to be aware of the requirements imposed by HICPA and can read more in this client alert.

No Hire Clause Called into Question

Many companies use restrictive covenant agreements with key employees to guard against economic harm to the company by an employee who takes a job with the company’s competitor and/or tries to persuade the company’s customers to stop doing business with the company. These are particularly common with sales staff. In Pennsylvania, these covenants will generally be upheld if they are narrowly drawn to protect the employer’s legitimate business interests and if the employee has been given meaningful consideration in exchange for agreeing to be bound by the covenants. To learn more about Noncompetes, visit our Navigating Noncompetes blog series in the AMM Employment Law Blog.

Companies recognize that merely doing business with other firms can also be risky when it comes to protecting their interests in employees and customers. Consequently, it has become customary to include “no hire” provisions in contracts to prohibit a party from hiring away the other party’s staff. These clauses are particularly common in agreements in the technology field and in non-disclosure agreements that parties often enter into when evaluating whether or not to begin a business relationship. The viability of these provisions is in doubt in Pennsylvania, where the Pennsylvania Superior Court struck down a no-hire clause in a service agreement earlier this year. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court has agreed to hear the case.

In Pittsburgh Logistics Systems, Inc. v. BeeMac Trucking, LLC, the trial court held that the no-hire clause was unenforceable because it prevented individuals from seeking employment with certain companies even though those individuals had not agreed to or been compensated for the restriction. It is important to note that in a separate action, Pittsburgh Logistics Systems (“PLS”), the company attempting to enforce the restrictions against BeeMac, was unsuccessful in its efforts to enforce the restrictive covenants contained in four employees’ employment agreements, each of whom left to work at BeeMac. The trial court concluded that the covenant not to compete was oppressive and overly broad since it had an unlimited geographic scope. The court viewed PLS as having “unclean hands” and refused to enforce the restriction at all.

The Superior Court agreed with the trial court and held that the no-hire clause was unenforceable as a matter of law. The Superior Court was influenced by the lower court’s holding that the non-compete covenants in the employment agreements were not enforceable, noting that it would be unfair for PLS to achieve the same result by using a contractual no-hire provision in its contracts with other companies.

Two Superior Court judges dissented, drawing a distinction between a no-hire provision in a contract between two companies and a non-compete clause binding employees. They reasoned that the no-hire clause did not restrict the employees’ actions; rather, the clause was a bargained-for restriction in recognition of the fact that BeeMac would have access to PLS employees and know-how. The dissenting opinion suggests that the correct analysis is whether the no-hire clause was a reasonable restraint on trade. Using that test, the dissenting judges would have enforced the clause and granted the injunctive relief requested by PLS to prevent BeeMac from “enjoy[ing] the benefit of its purported breach” and “leverag[ing] the specialized knowledge that PLS’s former employees acquired while under its employment.”

It will be interesting to see how the Pennsylvania Supreme Court views these issues when it hears this case. Stay tuned for further developments.

From a Litigator's Desk: Keep Your Business Laundry In-house

Business partnerships are like marriages; sometimes they work great from the start and before you know it you are celebrating a 25 year anniversary with a big party with all of your clients and customers in attendance. And sometimes; not so much. For reasons unique to business relationships and the personalities involved, business partners sometimes find they can no longer function together, no longer share the same vision, and can no longer tolerate sharing the responsibilities or benefits of common ownership. We refer to the painful and expensive process of separation as “business divorce”.

As in any divorce, emotions run high. The natural instinct is to assess blame and recruit those close to the business to one “side” or the other. Such recruiting efforts implicate disclosure of sensitive, often damaging information with the idea that inflicting pain will induce a desired course of conduct. Rarely is such an ill-conceived plan rewarded with success.

The reality is that preservation of the business as an asset should be the primary concern. Often that means preserving the opportunity for the business venture to continue operations without interruption, modification or additional added pressures attendant to disharmony. Whether the business can be divided according to an acceptable plan among the shareholders, sold as a going concern, or liquidated in an orderly fashion, continued successful operations are essential to return on the shareholders’ investment.

Successful operations are a function of several factors. First and foremost, management, employees, contractors and staff must be confident in the direction of the entity. Public disclosure of disputes among ownership breeds workforce instability, discontent, mass departure and potential competition on the part of key employees with the capacity to do so.

Customer relationships must also be protected. Instability will most certainly cause a client to search for an alternative provider of the same product or service. A client will not risk their own business by not addressing the potential impacts of instability in yours.

The bank can become concerned as well. Lending relationships are complicated. Often businesses obtain term loans or lines of credit which must be “rested” (reduced to zero) from time to time. A borrower’s options upon maturity can be limited and, notwithstanding a long and happy banking relationship, the bank may not be required to extend credit on the same terms and conditions. The bank may even take the position, under certain circumstances and certain loan agreements that the bank is insecure as a result of dissention thus forcing very difficult financial decisions.

Finally, in all likelihood, public disclosure of internal disputes results in the parties becoming entrenched in their respective positions such that a future together is impossible. Even a sale under such circumstances is likely to net less than market as a buyer is quick to assert pressure on one shareholder or the other in an effort to negotiate the best deal.

Really no good can come of a public airing or an internal dispute. Just like a married couple should not publicize their grievances on Facebook, business owners should take care to keep their disputes in house while seeking resolution through any number of mechanisms – at least until it becomes apparent that such resolution is not possible. Even then, the minimum amount of information necessary to effectuate a course of conduct should be disclosed in the least applicable public way.

Owner Liability – Piercing the Veil

A corporation or limited liability company provides multiple advantages to business owners which is why business lawyers so frequently recommend their use. Among the most significant of these advantages is limited liability, a concept grounded in the fact that the entity has a separate legal existence from its owners and therefore its obligations are not those of its shareholders or members. Of course an owner may voluntarily agree to be responsible for such obligations as, for example, would be the case if he or she guarantees the entity’s bank borrowing. The shield of limited liability is not, however absolute. It can be breached rendering owners financially responsible for the entity’s obligations. In Pennsylvania, as in most states, there is a strong presumption against ignoring the distinction between the entity and its owners. However certain conduct by business owners will result in the court’s “piercing the veil” – ignoring the distinction between the corporation or limited liability company and its owners. Generally, courts will pierce the veil when those in control of the entity use that control, or use the entity’s assets, to further his, her or their own personal interests. While there is no single test to determine when the piercing of the veil is appropriate courts look to many factors.

These include:

1. Is the entity undercapitalized?

2. Did the owners fail to adhere to requisite formalities such as holding shareholder and directors meetings and keeping appropriate records?

3. Was the entity insolvent at the relevant time?

4. In the case of a corporation were dividends paid or were corporate funds siphoned into the pockets of the controlling shareholders?

5. Was there a functional board of directors and corporate officers managing the affairs of the entity?

6. Was there substantial intermingling of the financial affairs of the entity and its owner(s)? 7. Under the circumstances, was the entity form used to perpetrate a fraud? Generally, the court will pierce the corporate veil when a review of these factors shows that the form is a sham, constituting a facade for the operations of the dominant shareholder or member making the entity effectively the “alter ego” of the individual(s).

What is a contract: Part 2: Offer, Acceptance, Consideration: What’s in it for you?

This post continues my series explaining the main elements of a contract, which are outlined on the attached infographic. My goal is to demystify some of these basic provisions to help business owners have a better general understanding of what they are signing.

Moving through the structure of a typical contract, next up is offer, acceptance, and consideration. Together, these clauses define what the offering party is promising to do (or refrain from doing) in exchange for the compensation the other party is willing to pay or provide. They basically comprise the tit for tat, or the meat of the obligations and privileges which are being offered. This is often referred to as a “meeting of the minds.” While this might seem obvious on its face, the devil may be in these details, so it is vital that you know and understand the specific nature of your obligations and be sure that they are sustainable, practical, and likely to result in a benefit to your bottom line or some other benefit to your business. So what can happen when parties fail to clearly memorialize their “meeting of the minds”? Here are a few scenarios that could result:

• The parties might become embroiled in a “battle of the forms”, particularly in the sale of goods context where a buyer submits a purchase order using their company’s form, and the seller responds using their own terms and conditions form containing different and/or additional terms.

• Parties can ask the court to apply certain legal theories to supplement the “four corners of the document” where the intent of the parties may not be clear from the contract itself. For example, even if there is no formal consideration, courts can apply the theory of promissory estoppel to enforce a party’s promise to do something if the other party relied on that promise to his or her detriment.

• Another equitable remedy allows the court to compel a party to make restitution if that party is enriched at the expense of the other party and the surrounding circumstances lead the court to conclude that it is unjust.

• Pennsylvania has a little-known statute called the Uniform Written Obligations Act, which allows the court to infer that consideration exists where the agreement includes language that clearly and expressly states that the parties intended to be legally bound by the agreement.

Stay tuned for Part 3 of this series, which will move to the next element on the infographic: Conditions.

Visit ammlaw.com to learn more about our contract review services, or Joanne Murray.

Before Signing That Commercial Lease – Have You Reviewed it with Counsel?

As a business owner, after spending countless hours researching and visiting commercial space, and finally finding the right location, you are often presented with a lengthy commercial lease. Many will focus on the rent and term of the lease, but overlook the other details. It is important to have an attorney review any commercial lease, whether you are entering a new lease or renewing an existing lease. Far too often, the business owner only consults an attorney when a problem arises – and they are surprised to find out that the terms do not mean what they thought at the outset.

Key areas that the business owner should review with their attorney are:

• Common area maintenance costs and calculations

• Confessions of judgment

• Responsibility for repairs

• Insurance requirements

• Subletting and assignment

• Legal options in the case of a breach.

Often there is room for negotiation, but even if there is not, you can gain valuable knowledge by consulting with an attorney so that you have a full understanding of your rights and obligations, and can plan accordingly.

While consulting with an attorney may result in a modest increase to the amount of legal fees associated with the cost of starting up a business, it is important for small business owners to recognize the long term impact of signing a lease that has not been negotiated, or at least reviewed, by an attorney, and may save money in the long run.

From a Litigator’s Desk: Key Questions to Consider in Commercial Litigation

People often ask, “What kind of lawyer are you?” After my stock (and feeble) comedic response of “a good one”, I often say I am a “commercial litigator”. I explain that our practice includes litigation of disputes which arise between businesses and business owners. Commercial litigation includes a wide range of potential issues ranging from business torts to breach of contract, both internal to a business entity, and between two or more separate entities. While there are a wide range of potential issues which must be considered, there are certain basic tenets which I always discuss with our clients before recommending litigation or taking on their representation.

First, do you have an agreement which might apply to the situation and, if so, what does that agreement say about your position? Agreements can come is various shapes and sizes, such as corporate by-laws, a formal shareholder agreement, a proposal combined with an acceptance or performance, or even a simple exchange of emails. Documentary evidence is key, as a litigator is challenged to explain why the written word should not be impactful.

Second, what is your goal? The kiss of death as to our representation is a client who says “it’s not about the money, it’s the principle”. When I was a young lawyer I had a mentor who gave sage advice when he communicated the firm’s policy that litigation was only appropriate when money was involved. He would politely say, “we don’t litigate over principle”. In many ways and in most situations that adage applies. However, in the corporate setting, sometimes the connection to money is not readily evident or direct such as with regard to disputes over corporate control or enforcing a covenant not to compete. In many situations, I caution stakeholders to take the long view and weigh the probable outcomes from a purely practical standpoint, taking care never to lose sight of their long range business goals.

Third, what is your capacity for litigation and business distraction? Litigation not only costs money in terms of attorney fees, accountant fees, experts and costs, but participation also requires commitment of a leader’s most valuable commodity; time. Business people are first and foremost concerned with business (daily operations, management and the bottom line). Litigation invariably requires substantial client involvement in developing strategy, reviewing pleadings, searching for documents, reviewing documents produced by other parties and preparation for testimony. I advise potential parties to litigation to think long and hard about the cost/benefit to the business of such an undertaking.

Fourth, what can you hope to recover or save; and what will it cost to do so? While a corollary to litigation about money, it is not the same question. The evaluation of potential cost is complex and issue dependent. In a recent case, settlement discussions in a commercial litigation setting were driven by the anticipated six figure cost to translate thousands of pages of information from Chinese characters to English. Costs of experts on any issue involving an opinion on issues ranging from the standard of care applicable to a corporate officer, to whether a machine functioned in the way represented, can rapidly accumulate. Unless there is a provision in an agreement which provides for the recovery of attorney fees or such recovery is otherwise permitted under law, those fees and costs are not recoverable.

The above is not to discourage litigation of bona fide disputes; of which we handle many. It is simply imperative that the lawyer and the client be on the same page as to expectations, risks and litigation management. These questions can assist in forming the framework of a solid attorney client relationship in a commercial litigation setting, which goes a long way toward developing realistic expectations, reducing the stress inherent in the process, and optimizing the chances of a successful outcome.